The Wealth of Individuals Part 8: Striking a Balance between Roth Conversions and Social Security

In Part 7 of this series, I repeated a bold assertion that I've made since the advent of Roth IRAs: they are perhaps the greatest gift ever offered to taxpayers by a government not known for its munificence toward those who produce wealth by saving and investing. Roth conversions, in which funds are transferred from traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs for the price of paying the tax now rather than later, magnify the wealth-creating attributes of Roth IRAs. This issue of Wealth Creation Strategies is devoted to showing how Social Security benefits can be coordinated with Roth conversions, which significantly increase our ability to avoid absurdly high real tax rates that often slam Social Security recipients. Because most taxpayers are unaware of what may be the most effective tax and financial tools for preserving and amassing wealth, this is Part 8 of our "Wealth of Individuals" series.

"Income Averaging" is Back! Using Roth Conversions to "Average" Your Own Income

Back when marginal income tax rates were as high as 90% the great boxer Joe Louis, who earned nothing in his early years, had trouble paying his taxes when he finally hit it big. Because this type of scenario was seen as inequitable by many, Congress eventually acted and created a way to calculate the tax on income as if it had been earned over a several year span, effectively lowering the marginal tax rate when income skyrocketed. It was never a perfect system—it didn't work in reverse (so if your income collapsed, tough luck) and only sort of averaged income over five years and, towards the end of its legislative life, three years—but it was better than nothing. Income averaging was abolished as part of the compromise leading to the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which flattened tax rates, lowering the advertised top marginal rate to 28% and making income averaging seem superfluous.

Income Averaging never really went away

Although its been 25 years since "income averaging" was eliminated as an optional method by which to calculate income tax, many mature clients still ask, "Wont income averaging save on my taxes?" Yes, but only our own privatized version. Even before Congress eliminated the legislated, mechanical method, I counseled clients to do everything they could to "smooth" income, since income averaging helped those who had several successive low income years followed by one or two years of substantially higher incomes, but not those whose income fluctuated in erratic fashion or simply plummeted. If you had $50,000 of income in each of years one and two, zero in year three and $50,000 in year four you were not helped by this method of calculating tax. I often pointed out that the tax on $50,000 of income was a lot more than twice the tax on $25,000; therefore, it was cheaper tax-wise to realize and pay tax on $25,000 of income in each of two years rather than zero in the first year and $50,000 the next.

An example of potential tax savings by self-income averaging

| Yr 3 | Yr 4 | vs. | Yr 3 | Yr 4 | Savings | |

| Income | $0 | $50,000 | $25,000 | $25,000 | ||

| Tax, single | $0 | $6,300 | $1,900 | $1,900 | $2,500 |

For many, such "self-smoothing" of income was (and is) a challenge to actually accomplish. Some methods of doing so, such as deciding to purchase business equipment in one year and not the next and funding or not funding retirement plans, are obviously limited in application. However, it's far easier if one is able and willing to make use of Roth conversions.

The benefits of spreading income especially apply to those who will receive Social Security, or are already receiving it

But first, who benefits by averaging income? Those who are in low tax brackets temporarily and whose rates are expected to climb, and those in high tax brackets whose rates are expected to drop. The first group is the focus of this article. Who comprises this group?

1. The temporarily unemployed or under-employed

2. Those who go back to school

3. Those with fluctuating incomes who are earning less now than we expect later (for example, actors, contractors and real estate brokers)

4. Pre-retirees in the 15% marginal tax bracket whose tax rates will climb due to the way Social Security benefits are added to taxable income, which comprises many more of you than you may think

5. Retirees whose last chunk of income is taxed at 15% marginal tax rates when married, but who are expected to be slammed with 27.75% and 46.25% marginal tax rates once widowed

Two factors have combined to dramatically increase our ability to "self-average" income. First, traditional IRAs (or IRA rollovers from 401ks and other retirement plans) are increasingly commonplace and larger than ever. Second, the availability of Roth conversions—the transfer ("conversion") of funds from a traditional to a Roth IRA for the cost of tax (but never a penalty) on the funds transferred—which were first allowed in 1997 and expanded in terms of eligibility to everyone in 2010. However, because of an aversion to paying tax before required, few taxpayers have taken advantage of this opportunity. It seems to runs contrary to nearly everyone's mindset: "always defer tax." Yet, under the right circumstances paying the tax now via Roth conversions can be immensely profitable. To whet your appetite, one retired client's income dropped by $15,000 one year and he did a $15,000 Roth conversion at a tax cost of $1,500. If he had done a conversion in any other "normal" year, because of the way Social Security benefits are taxed, the cost of the identical conversion would have tripled. Wow. And now the Roth will grow (hopefully) until he or his heirs withdraw it tax-free. Double-wow.

Several variables must be considered in any strategy involving the acceleration of income tax:

1. The relative marginal tax rate between any two or more years and, specifically, the percentage increase

2. The number of years of deferral to the higher marginal tax rate (but, as we will show in discussing the wealth neutrality of Roth conversions, timeframe is irrelevant when accelerating tax via this method)

3. An estimate of what you can earn risk-free on the funds in the interim, or if you are in debt, the cost of continuing to borrow the amount of tax that can be deferred

The tax now may be a heck of a lot less than later

Let's start with what may seem an extreme case, but one that hits many taxpayers in real life. Say you have a choice of paying tax on $30,000 of income this year at a 15% rate or next year at a 45% rate. In which year would you choose to include the income? The answer should be obvious. What if the 45% rate doesn't kick in until 10 (or 20) years later? Since the odds of tripling your tax savings in ten years by electing to defer the tax are remote, the answer to this question should also be obvious: you'd much rather pay $4,500 in extra tax this year than $13,500 ten years from now (and likely even 20 years) on that same $30,000 of income.

Conversely, if you can shift income to next year and pay the same rate or less as this year, obviously you'll (wisely) choose to defer the income. However, the strategy isn't obvious if the rate next year is higher even by a small margin. (While the dollar amounts here are not large, please bear with me because the idea is crucial.) For example, if you have a choice of realizing $10,000 of income this year or next year, when you expect the tax rate on that income to increase from 15% to 16% (so the tax increases from $1,500 to $1,600), in which year would you choose to recognize the income? A 1% increase in the tax rate doesn't seem like much, but it is. The cost is 6.7% of the $1,500 which, when all you can earn on the money safely is .05%, is expensive. (On the other hand, if you're paying 18% on credit cards, by all means defer the tax and pay down your debt.)

Decision-making gets more complicated when deciding whether to realize income and pay tax now or, say, twenty years from now. We have no idea what tax rates will be, not only for you specifically but overall. Will taxes increase? Will your income increase by enough to subject you to higher tax rates even if overall tax rates remain the same? What will you be able to safely earn on funds saved now, but which will be spent on taxes later? All we can do is guess.

These questions have gravitated front and center over the last several years, as I began seeing increasing numbers of clients subjected to confiscatory high "phantom" (but real) tax rates due to the Social Security phase-in provisions. This has been the key impetus in urging many clients to "elect" to pay tax on some tax-deferred retirement income now, specifically via Roth conversions and especially when tax can be paid at 15% and lower rates—and occasionally at combined federal and state rates of as high as 35%. To appreciate the potential long-term tax savings using this strategy, it's essential to understand two key items: one, the wealth-neutrality or mathematical equality of converting to Roth IRAs for those in the same tax bracket now and later and two, the gory details of how Social Security benefits are subjected to tax as other income and Social Security benefits increase.

Converting now or later leaves you with identical sums if your tax rate is the same now and later

The first item is a mathematical equality: the after-tax income created by converting a traditional to a Roth IRA is the same as the after-tax income by withdrawing from the traditional IRA years later if your tax bracket is the same in both years. If, say, you convert $20,000 to a Roth IRA at a 25% tax rate, netting $15,000, and let the proceeds double inside the Roth, you end up with $30,000 (keep in mind that, done right, Roth IRAs grow and are withdrawn entirely tax-free). If you leave the $20,000 inside the IRA and let the proceeds double (identical investments, same time-frame), you end up with $40,000 less the 25% tax on the withdrawal, or $30,000. Thus traditional IRAs and Roth IRAs are mathematical equals at any given tax rate with identical investments over any given time-frame, so long as the value increases and you follow the easy-to-meet rules. (You are even better off if you can pay the tax from other non-IRA funds when you convert.) The corollary to this is you come out ahead by converting to a Roth to the extent you are subject to lower tax rates now.

Taxation of Social Security benefits can result in a much higher tax rate than you ever imagined

The second consideration is the method by which Social Security benefits increase overall taxable income. Since 1984, every dollar of income in excess of a "base amount" of $25,000 for single filers and $32,000 if married filing joint has required that $.50 of Social Security benefits be added to income until 50% of Social Security benefits are taxed. (That "base amount" is, generally, non-Social Security income plus ordinarily non-taxable municipal interest income plus 50% of Social Security income.) In other words, every dollar of income is taxed as if you earned $1.50 once income exceeds those threshold amounts. Because this "base" income has never been indexed for inflation, markedly fewer retirees were subjected to the phase-in in 1984 than today. In 1984, median household income was $22,415. Today it's about $50,000.

To make matters dramatically worse, beginning in 1994 Congress decreed that a new phase-in provision would be added to the 50% phase-in: once "base" income exceeded $34,000 ($44,000 married) $.85 of Social Security benefits would be added to income for every additional dollar of non-Social Security income until 85% of Social Security benefits are taxed. Because the "base amount" for this phase-in is generally defined as non-Social Security benefits plus ordinarily non-taxable municipal interest income plus 85% of Social Security benefits, every dollar of income over these limits is taxed as if you earned $1.85. (Is your head exploding yet?) This, likewise, has never been inflation indexed. Median household income in 1994 was $32,264.

Additional income over the "base amount" increases the amount of Social Security benefits on which you must pay tax

|

Filing Status |

50% Base Amount |

85% Base Amount |

|

Single |

$25,000 |

$34,000 |

|

Married Filing Joint |

$32,000 |

$44,000 |

|

Each additional $1 of income is taxed as if you earned: |

$1.50 |

$1.85 |

These "base amounts" have never been indexed for inflation. Here are what the numbers would be for 2010 had they been appropriately indexed:

|

Filing Status |

50% Base Amount |

85% Base Amount |

|

Single |

$53,600 |

$72,900 |

|

Married Filing Joint |

$68,600 |

$94,350 |

How did they slip this in under almost everyone's radar?

There are surprisingly few other advisors focusing on the idea that we should deal with and, where possible, reduce the long-term impact of the phase-in of Social Security benefits and resulting confiscatory high marginal tax rates on retirees. I wondered how this issue largely escaped even my attention until the early-2000s. At the risk of being repetitious, I finally figured out that five factors, in conjunction with one another, explain how it slipped by nearly everyone:

1. Congress decreed back in 1984 that up to half of Social Security benefits would be subject to income tax once other income plus 50% of Social Security benefits exceeded those magical $25k/$32k thresholds. These have never been adjusted for inflation.

2. In 1994, Congress decided to subject up to 85% of Social Security benefits to tax (even though that additional 35% has already been taxed once) under a "phase-in" provision once other income plus 85% of Social Security benefits exceeded $34k/$44k. These have never been adjusted for inflation.

3. Retirement plans, including IRAs, 401(k)s and their progeny, IRA rollovers (many of which didn't even exist until about 1980), have substantially increased in size. Eventually, every pre-tax dollar in these plans will be included in income. The only question is who will pay the tax (you or your heirs), when and at what marginal tax rate. Distributions from these plans have increased retirement income for many, subjecting increasing amounts of Social Security benefits to tax.

4. Social Security benefits have ballooned because (unlike the levels at which they increase taxable income) they have been adjusted with Consumer Price Index inflation. Thus, as income and Social Security benefits rise, Social Security is increasingly being phased in and over increasing expanses of income. For example: one client's Social Security benefits, which totaled $11,300 in 1994 and to which as much as ($11,300 x 85% =) $9,600 was subject to tax, increased by more than 50% to $17,000 in 2010, subjecting as much as (85% of $17,000 =) $14,450 to tax. This client's other income plus half of Social Security wasn't high enough in 1994 to be subject to the phase-in, but was partially subject in 2010, resulting in a marginal tax rate of 46.25% on a small (but not immaterial) "chunk" of income. (Even during the "low-inflation" 2000s—the ten years from 2000 through 2010—Social Security benefits increased by about 31.5%.)

5. The fact that your head is exploding may provide a clue to this reason: only mathematical geniuses understood the calculations required to determine taxable amounts of Social Security benefits (not to mention their long-term ramifications), which allowed the government to get away with this sleight of hand tax increase.

No one saw this coming. Consider the likelihood that even with low inflation many more seniors are going to be subjected to confiscatory rates on increasing "chunks" of income.

Couples are in a good position to optimize conversions—before one dies

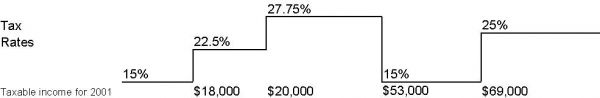

Already, a large number of married seniors who are nominally in the 15% tax bracket are subjected to a "phantom" (yet very real) tax rate of 22.5% as 50% of Social Security benefits are phased in (15% plus 50% of 15% = 22.5%) and 27.75% as 85% of Social Security benefits are phased in (15% plus 85% of 15% = 27.75%). (Remember the comment on exploding heads?)

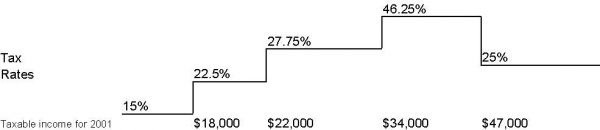

It gets considerably worse for widowed and other single seniors. Far more often than back in 1994, Social Security benefits are being phased in under the 85% phase-in rules when the single taxpayer enters the advertised 25% tax bracket, subjecting such seniors to absurdly-high real (25% plus 85% of 25% = ) 46.25% tax rates on a "chunk" of their income (for example, the client five paragraphs up). This is one of the reasons I'm encouraging many clients to pay all the tax they can at 15% rates, especially via Roth conversions.

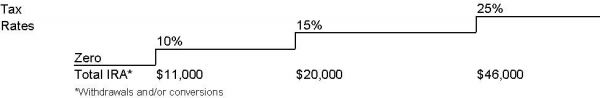

Chart 1: Common real tax brackets for married seniors collecting Social Security. Those near the end of that phantom (but real) 27.75% bracket should consider realizing additional income, "using up" the 15% bracket that follows. Keep in mind, the 22.5%, 27.75% and second 15% tax brackets vary from couple to couple as a function of their combined total Social Security income and various deductions. In this instance, the Social Security income totals $27,000.

Chart 2: Common real tax brackets for single seniors collecting Social Security. Those currently married who can take advantage of the 15% bracket in the chart above should study the chart below. The particular client used in this example received $22,000 in Social Security benefits.

Because the phase-in subjects single filers to exorbitant tax rates at such low income levels, married couples should consider realizing income via Roth conversions (or other means, if applicable) years before either Social Security or Required Minimum Withdrawals (RMDs) from IRAs and other retirement plans begin. Because of the detrimental effect on real marginal tax rates, delaying the start of Social Security should also be considered by many retirees (see the next article). Those up to age 70 who are already collecting, depending on a number of factors described in the next article, should consider stopping Social Security for a period (during which time future starting benefits increase by over 7% per year) and, even if they don't stop, taking additional income at the "real" 15% tax bracket to the extent possible, because when one spouse is gone the survivor will more likely be subjected to 22.5%, 22.75% and 46.25% tax rates on various "chunks" of income, even at relatively low income levels.

A closing note for my libertarian-leaning friends and critics: I fully recognize that Social Security is essentially a Ponzi scheme (new "investors," in this case, perversely enough, children of those receiving benefits are paying old "investors," the parents). Worse, it has created enormous reductions in private savings and, because private savings are the root of wealth, dramatically reduced the rate of growth in overall living standards. I am quite aware that even Ponzi schemes run by a government that theoretically can print its way out are likely to blow up (see the top story, "The Problem: Excessive Unproductive Debt," in issue # 42 of Wealth Creation Strategies at www.dougthorburn.com/newsbyedition.php). A few of you so strongly object to the current system that when eligible, you will not accept benefits. I've suggested that you take and donate the after-tax proceeds to free-market think tanks working to replace the system, or to politicians who support replacing it. Make no mistake: I do not question that the current system is unsustainable without increasing Social Security payroll tax rates to levels that will greatly reduce productive endeavors (at some point, serfs say "to hell with this!"), leading to an even greater reduction in living standards. I also understand the system was imposed at a time when life expectancy was 62 and every recipient was supported by some 30 workers at a fraction of its current cost in terms of both tax rate and income on which it is imposed. A privatized or partially privatized system, as Chileans and even Swedes now have, would be vastly superior. However, we need to deal with reality: until replaced with a private system, it's what we have. I believe that if the system collapses of its own weight, you have little to lose by engaging in the strategy outlined (especially at 15% tax rates). In addition, the overriding ideas presented here can likely be applied as profitably under a more sustainable ("robust") system. Barring a complete collapse, the relative differences in Social Security benefits based on age will likely be similar under any replacement system, certainly for those close to retirement. Therefore, the strategy described in the next article—delaying the start of Social Security—is probably viable regardless of future changes, which will likely affect only younger workers. Besides, we can only plan for what we know. Hedge your risks for what we don't know, which means don't rely on Social Security or any other government program for survival.

For additional thoughts and support for many of the ideas presented here, be sure to re-read the articles in the following issues of Wealth Creation Strategies:

- #21, p. 4 "Income Averaging: Making the Best of a Low Income Year"

- #25, pp. 4-5 "I Can't Contribute to My Roth IRA Because..."

- #29, pp. 4-6 "What's my Tax Bracket: A Focus on Social Security Recipients"

- #35, pp. 2-4 "Traditional IRA-to-Roth Conversions: When is a Conversion Right for You?"

- #40, pp. 1-6 "Understanding and Using the Roth Conversion to Create Wealth"

- #43, p. 7 "More Myths of Roth Conversions"

all available at: www.dougthorburn.com/newsbyedition.php.

Even More Myths about Roth Conversions

Financial adviser Ric Edelman, chosen by Barron's for seven straight years as one of America's top 100 independent advisers and ranked number one in both 2009 and 2010, who has written seven financial books and whose firm manages more the $6 billion in assets, was recently quoted in Bottom Line: Personal as saying that converting to a Roth IRA "does nothing to increase your wealth."

While true for a taxpayer in the same tax bracket now and later (an example he uses; he fails to mention those whose tax brackets may change), this is not the "ideal" person to engage in the conversion strategy. This sort of sweeping generalization reduces the odds someone will think "conversion" when not only appropriate, but lucratively so. We can think of at least two clients who missed fabulous opportunities last year, perhaps because people take seriously such generalizations by well-known advisers who should know better. One client, whose "normal" tax bracket is expected to remain at 15% federal and a few percent state, could have converted $25,000 and paid $1,000 in total tax. Another could have converted $36,000 with zero tax liability and an additional $10,000 at a 20% tax rate; his marginal tax bracket had been 35% for several years in a row and could easily go back to that level.

Another misconception is the idea you can't touch a conversion for five years. If you are over 59 ½, yes you can. You can't touch the earnings for five years from each conversion, which is a huge difference when earnings are tiny. And if you do, what's the worst that happens? You pay the tax, which would be minimal.

If you are ever told or read anything negative about Roth conversions, please let me know. I'd be delighted to debunk another likely myth.

Several Reasons to Delay the Start of Social Security

Roughly 45% of eligible U.S. workers start taking Social Security at age 62 and nearly two-thirds begin collecting before the new "normal" Full Retirement Age of 66, at which point fully 95% of those eligible have begun collecting (including even those still working or with other means of support). Although Social Security is age-neutral in terms of the present value of lifetime benefits across the broad population (which means that if people knew the unknown and considered statistical probabilities half would begin collecting after age 66), individuals can engage in what those in the insurance industry call "adverse selection:" people with short life expectancies can increase the present value of their likely lifetime benefits by starting to collect earlier and those expecting a longer life can do so by starting later. As you will see below, starting later may be beneficial for a higher-income spouse whose family histories and current health suggest that either spouse will probably live past age 82. Many (statistically, half of the population) should therefore consider starting Social Security sometime after reaching age 66 and, surprisingly, as late as age 70. This is even truer if Roth conversions can be done at low tax brackets in the interim (recall from the article above the mathematical equality of Roth conversions and traditional IRA withdrawals at equal tax rates). Let's take a look at this idea step-by-step.

Social Security is a joint-and-survivor lifetime annuity

First, view Social Security as a lifetime annuity. The longer you delay the start of any annuity, the higher the initial and all subsequent payments. Therefore, the longer your life expectancy, the more likely it will pay to wait to begin collecting (up to age 70, at which point initial Social Security benefits stop increasing, except for inflation adjustments). Your annuity increases by a bit over ½ of 1% for every month you delay the start of Social Security, or slightly over 7% per year. Because the 7% per annum is compounded, delaying the start from age 62 to 66 (under current law) results in a roughly 33% increase and delaying from age 66 to age 70 provides an additional nearly 33% increase. The total increase by delaying from age 62 to age 70, again due to compounding, is about 77%.

Second, unlike most annuities, Social Security is inflation-adjusted. Therefore, any return on "investment" by waiting to collect is correctly viewed as an after-inflation return.

Third, while private (and far more realistic) annuities make you take a "haircut" (a lower monthly payment) if you want the non-annuitant (in this case, the lower-income spouse) to collect the same amount as the annuitant (in this case, the higher-income spouse) if the latter dies first, there is generally no such reduction under Social Security. It is a joint and survivor-based system that allows the lower income spouse (assuming certain requirements have been met, including neither spouse being a government pensioner) to collect the higher-income spouse's full Social Security benefits should the latter spouse pre-decease the former. Thus, the question for purposes of deciding when to start collecting is generally not how long each spouse will likely live, but rather how long either spouse will likely live. (While I think it may overstate life expectancies, you can get your own estimate at www.livingto100.com).

Fourth, although there are huge systemic risks, from a practical point of view in terms of this analysis we should view this "annuity" as risk-free. Therefore, the relevant question in comparing outcomes and deciding your breakeven points in terms of life expectancy is what "risk-free" return on investment am I willing to accept? A reasonable return on a risk-free investment has long been considered to be 3% or less. If you expect stock prices to return 6% from current levels (with great risk) and inflation to average 3% over an extended period, an after-inflation return on investment of 3% from a "risk-free" annuity is a terrific deal (which is one reason why we can't expect it to last in its current form).

Because there are variables and assumptions, go with the odds

Fifth, before running the numbers and attempting to optimize the present value of your lifetime annuity, other variables must be considered. If you have no other means of support, other factors are irrelevant. Using 3% as the return on "risk-free" investments is irrational if you need additional income now to prevent you from going into debt (or paying down debt) that costs you 18% (and, arguably, anything much more than 3% after-tax with the possible exception of a home mortgage). On the other hand, until you reach Full Retirement Age (currently 66), starting to collect while earning more than the amount allowed (presently about $14,000 per year), which results in having to repay $1 of Social Security income for every $2 of earnings over that amount, is probably unwise (although you slowly recoup that lost money in the form of an increased payment beginning at age 66).

Sixth, to compare apples with apples we need to determine the "future value" of the income stream from the Social Security annuity using a "reasonable" rate of return. Vary the rate of return and you will get different answers to the question, "When should I begin to collect?" For the reason explained above, we'll consider 3% as more than "reasonable."

The question, using this set of assumptions, can be boiled down to: at what age is the future value of an income stream earning 3% per annum of "x" dollars from age 62 and "x times 1.33" dollars from age 66 equal? This tells us the breakeven age-the age to which you must live in order to justify delaying the start of Social Security to age 66. Using this formula, the breakeven age is 82. Therefore, if either you OR your spouse expect to live to at least age 82 the higher-earning spouse should delay the start of Social Security until at least age 66.

For example: if the higher-earning spouse's Social Security will be $1,688 at age 62 and $2,250 at age 66, the future value of $1,688 per month invested at 3% for 20 years (until age 82) OR $2,250 per month invested at 3% for 16 years (until age 82) is worth about $557,000. If you reduce that 3% factor to 2%, the breakeven point is about age 80; if you increase it to 4%, breakeven is reached at slightly over age 84. Choose your assumptions wisely.

Taking this further—remember, I began this piece with the seeming radical assertion that many more people should delay the start date past age 66—at what age does the future value of an income stream earning 3% per annum of "x" dollars from age 66 equal the income stream of "x times 1.33" dollars from age 70? The answer is a tad over age 88. Obviously you can do rough extrapolations for expected ages in-between, or actually run calculations. For example, if you expect to live to age 85, the optimal age to begin collecting Social Security using these assumptions is age 68 or so. If you throw up your hands and admit you have no idea how long you will live, you might want to hedge, keeping in mind that Social Security can be viewed as an annuity and, therefore, as longevity insurance (which insures you won't outlive your income). Ask yourself, "What if I live that long and run out of other funds, or I'm actually healthy enough to enjoy life?"

Client changes her plans and likely adds a substantial amount to her net worth and income

Now let's take a couple of real life clients, who we'll call clients # 1 and # 2. Client # 1, who is single, told me she was planning on retiring in a few months at age 66 with $400,000 in her 401(k) that will become a rollover IRA. She intended to begin collecting Social Security upon retirement.

I asked how long she expects to live using her best estimate based on family history and current health. She didn't hesitate: into her 90s. I suggested she reconsider her plan. When I explained the assumptions and breakeven points described above, she immediately glommed onto the idea, but asked other than $5,000 of income from another pension, what would she live on in the meantime? I asked how much she has in taxable accounts outside of her 401(k). About $200,000, but she didn't want to run through any of that money. I asked why not? By living on those funds to the extent needed, she could essentially "purchase" a larger Social Security annuity, increasing her inflation-adjusted Social Security benefits for life by roughly 7% per year, compounded, for every year she delays the start. Plus, I explained, she's got the $400k. But, she protested, that's taxable! Yes, eventually the entire $400k will be included in income. The only question is, at what rate, when and by whom (her or her heirs)?

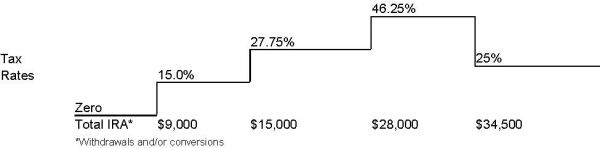

Her Social Security benefits would start at $26,400 yearly at age 66. Running the calculations and assuming her itemized deductions would remain at $14,000 (which they won't, making the recommended strategy even more profitable than presented here), we determined she could take $9,000 in IRA income at a tax cost of zero. With the current tax rate regime, she could take an additional $6,000 at a 15% rate (a phantom but very real rate while she's subjected to a 10% advertised rate). However, any additional ordinary income (IRA withdrawal or otherwise) over $15,000 would cost a minimum of 27.75% because at that point every additional $1,000 of income subjects an additional $850 in Social Security to tax, so at the 15% "advertised" bracket she'd pay 15% of $1,850, or 27.75% "real" tax. She'd hit the exorbitant 46.25% rate at about $28,000 in IRA withdrawals (or other income), where she'd remain for about another $6,500 in income (at which point 85% of her Social Security benefits would be taxed and her real tax bracket would drop to the advertised one of 25%). The Required Minimum Withdrawal (RMD) at age 70 ½, assuming the IRA stays at $400k, will be about $15,000. So, while the first $9,000 will be tax-free, the additional $6,000 she must withdraw just to take her RMD will be subject to a 15% real tax rate and anything over that (which will likely occur as the RMD increases over time) will be subject to that awful 27.75% phantom tax rate. In addition, as her itemized deductions decrease, the amount of withdrawals subject to the lower zero and 15% rates will decrease.

IRA withdrawals and/or conversions and their phantom (real) tax rates for client # 1 before she changed her plans

I suggested we take advantage of Roth conversions for the next four years before starting Social Security.

I showed her we can convert nearly $46,000 per year at a yearly tax cost of about $4,600 federal (and an annoying $1,200 CA state), or about 10% federal (and 2.6% state) average tax rates (with a top marginal rate of no greater than 15% federal and 8.3% state). Over a four-year conversion period, we could convert nearly $184,000 of her IRA, which would reduce the value of her traditional IRA to about $216,000, from which her first RMD will be about $8,000. I also explained her Social Security benefits will increase to over $35,000 (plus the interim inflation) per year at the start.

IRA withdrawals and/or conversions and their phantom (real) tax rates for client # 1 after she changed her plans

Her eyes got really big.

Because there are so many variables, it's impossible to say how much income tax she'll save over her lifetime (and, therefore, by how much her potential lifetime spending and final net worth will increase). However, assuming 5% growth in an IRA and withdrawing only RMDs, the account balance continues to grow into the early 80s (withdrawals based on RMDs are often less than the growth for the better part of a decade plus), while the divisor that determines the RMD shrinks. If she began taking RMDs at age 70 ½ and did no Roth conversions and the account grew by just 5% per annum, she'd still have close to $400,000 in her IRA at age 82 and the RMD would be over $23,000 (at least $8,000 of which would be subject to that phantom but very real 27.75% tax rate). After a series of Roth conversions leaving about $216,000 in her traditional IRA, the RMD would be less than $13,000 at age 82. The tax on the $184,000 of Roth conversions would run about $23,000, while this income stacked on top of future RMDs without Roth conversions would likely run north of $50,000. The probable future tax savings alone is equal to a year's worth of Social Security, which arguably reduces her breakeven age by at least a year for this strategy to work in her favor (reducing the breakeven age from 88 to less than 87).

The cost of increased taxes aggravates the trauma of a death in the family

Client # 2 is a married couple, who benefit by realizing IRA income via Roth conversions and paying the tax on it now rather than later when, after the first death, the survivor's tax bracket will likely skyrocket. They can increase their ability to pay tax at low rates by deferring the start of Social Security, from which they will also likely benefit.

They have $57,000 in pension and investment income, $150,000 in taxable accounts and $300,000 in his traditional IRA. He was determined to start Social Security at age 62. I asked how long each is likely to live based on current health and family history; he figures one of them will reach 85 and it won't be him. She's the lower income earner and three years younger, which makes 88 the relevant age for purposes of deciding when he should start taking his Social Security benefits.

I asked if he'd like to help his widow maintain the lifestyle to which she had become accustomed and he responded, emphatically, "absolutely." I explained that for every year he deferred collecting Social Security, he was increasing their lifetime annuity by over 7% (remember, the survivor continues to collect his benefits). I explained that if he began collecting Social Security now he could take only about $8,000 per year from his IRA at the lower tax brackets; yet, assuming no growth in his IRA in the intervening years the RMD will start at about $12,000 at age 70 ½. I explained there's a wonderful and cost-effective way to reduce the RMD to $8,000: he could defer the start of Social Security for four years (considering their life expectancies arguably on the too-conservative side) and in the meantime convert $30,000 of his IRA yearly at a tax cost of 15% federal (and an annoying average state tax of 6%). He'd convert $120,000 for a total cost of about $25,000. If both live long enough (remember, RMDs often increase into one's early 80s), the tax on that income could easily surpass $37,000 (31% average tax rate); if either one of them dies when the RMD is still large, the tax on that chunk of the IRA could easily hit $42,000 and conceivably surpass $60,000 (46.25% federal tax rate and several percent state if he dies first and the pension gets chopped in half). He opted to delay the start of Social Security, commence conversions and live on savings (which, when you think about it, are really being "shifted" to his Roth IRA for the price of taxes at substantially lower rates than those same funds will likely be subjected to later in life). The bottom line is by doing Roth conversions they are increasing total savings relative to what they would otherwise be and, at the same time, increasing their lifetime Social Security annuity.

If you stayed with me this long, you've learned a lot. On a re-reading, you may become less confused and learn even more (many clients have admitted they got more out of the client letter on a second and even third reading than the first). This is admittedly tough stuff but, as I hope you agree, well worth the slog. Through a combination of Roth conversions and delaying the start of Social Security where appropriate, many of you may increase your lifetime earnings by tens of thousands of dollars and also realize tax savings in the tens of thousands.